ANATOLIAN WOMEN THROUGHOUT THE AGES

Excerpt from the Introduction to the Cataloque of the "Woman in Anatolia, 9000 years of the Anatolian Women Exhibition" by Prof. Günsel Renda. (Ministry of Culture Publication, İstanbul, 1993)

Within the context of the history of mankind spanning over several million years of human evolution, the story of the Anatolian woman illustrates woman's creativity, productivity and prominence in all the civilizations which have flourished in Anatolia. The woman appears as a goddess with creative and productive powers, as a ruling monarch, as a patriotic citizen, patron of the arts, teacher, writer and artist, and at all times as a mother guiding her family.

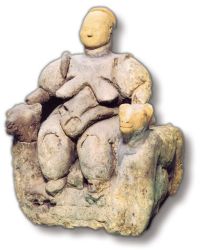

Figurine of a woman, Early Bronz Age, last quarter of 3rd mill. B.C.

Baked clay figurine depicting mother-goddess

Prehistory-Iron Age

(7th millennium BC-7th century BC)

The hunting and gathering communities of the Upper Palaeolithic Age become aware of sexual differentiation and fecundity of women for the first time, and therefore associated women with the concept of fertility. During the Neolithic Age, when human beings began cultivating the land and establishing permanent settlements, objects unearthed at such ancient settlements as Çayönü and Nevali Çori in southeastern Anatolia show that these people harboured religious beliefs centered around a fertility cult in which the woman was the predominant element. Finds at the Neolithic settlement of Çatalhöyük, the largest in Anatolia, demonstrate that at the end of the 7th millenia B.C. belief in the supernatural made way for religious faith in the true sense. It was Neolithic man who first drew a connection between the idea of creation and sexual relations and birth, manifesting this concept in a divine family consisting of god, goddess and child. The female goddess was the dominant element in the equation, with power of birth, life and death, and was seen as the protector of all creatures.The role of the woman in both religious beliefs and the family was equally preeminent a thousand years later, as proved by finds at Hacilar.

With the advent of the Bronze Age, at the end of the 4th millennium B.C., coinciding with the formation of the first towns and political organization, the role of men in society took on new significance, although the woman remained the symbol of fertility and the cult of the mother goddess continued to flourish. The mother goddess was now associated with the sun, as we can see from finds at Kültepe, where the sun goddess and her family had come to dominate the pantheon. When cuneiform writing was introduced into Anatolia in the 2nd millenium, ushering in the historic age, the names of Anatolian gods and goddesses were recorded in tablets and seals. These documents shed light on the status of the Anatolian woman at this time. Queens enjoyed substantial authority in administration and commercial life. Ordinary women were also able to pursue certain professions and to earn their own living.

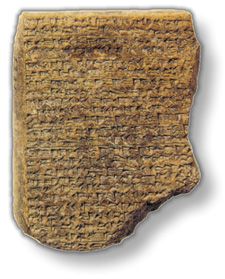

Letter from Egyptian King Ramses II to Hittite Queen Puduhepa, Hittite Empire, 13th century B.C. language: Akkadian.

In the middle of the 2nd millennium, kings and queens of the Hittite Empire which ruled most of Anatolia enjoyed equal powers and also served as chief priests and priestesses in the religious hierarchy. Several Hittite queens set their stamp on the nation's history in the course of performing their official and religious duties, either together with the king or independently, such as Queen Puduhepa.

Hittite legislation attached great importance to equality between men and women as we learn from written documents concerning property, marriage and criminal law which applied to the common folk as well as to the nobility.

In Hittite mythology, the chief goddess Hepat, the sun goddess of the city of Arinna, undoubtedly was a later embodiment of the already ancient mother goddess of Anatolia. After the collapse of the Hittite Empire the Phrygians, who had established a kingdom in Central Anatolia, also adopted Anatolia's ancient cult of the mother goddess, transforming the Late Hittite chief goddess Kubaba into the Phrygian Cybele.

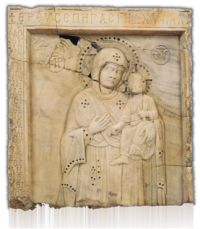

Icon with relief of Mary and Jesus, Byzantine period, end of 11th century

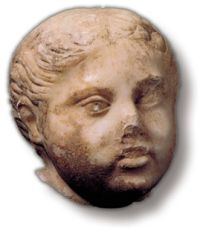

Head of Vedia Phaedrina, Ephesus Roman (Severan) period.

Fig.11: The Harem

Aphrodite Anadyomene, Yalova-Çiftlikköy late Hellenistic period, 1st Century B.C.

Dancing Nike, Myrina (Kalabaksaray)Hellenistic period

Greek-Roman-Byzantine periods

(7th century BC-15th century AD)

The cult of the mother goddess which had existed in Anatolia since the Neolithic Age dominated religious life in Greek settlements such as Ephesus in the 6th century B.C., where Artemis was the latest embodiment of the mother goddess. Even Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty in Greek mythology, appears in the role of mother with her son Eros in many works of art. Artemis and Aphrodite were the patron goddesses of several cities even in late periods, as demonstrated by the statues of these two goddesses found at Ephesus, Aphrodisias and Perge.

Examination of the role of women in Greek society in Anatolea reveals that women, as citizens, enjoyed fundamental liberties, that the family was held in high regard, and monogamy was an accepted practice. However, the woman's world was confined to the house, and in large households women lived in separate quarters. Nonetheless, famous poetesses and women painters emerged among the women of aristocratic and cultured families. The famous poetess Sappho of Lesbos is an example.

Where the role of women in government is concerned, the Carian Kingdom in Anatolia stands out, ruled on several occasions by queens, such as Artemisia I and II, after the death of their husbands. Queen Appollonis, wife of Attalos I of Pergamum and Queen Sinope and Queen Amastris of the Black Sea region in the 3rd century B.C. were famous as patrons as well as rulers.

During Roman times, women seemed to have enjoyed more freedom than during the Greek period and to have been more active in life outside the home. Although they did not have political rights, they were under the protection of Roman law. They pursued a variety of professions, even engaging in trade. Many Anatolian women of the Roman period are remembered as patrons, such as the priestess Modesta who built many parts of Side, Antonia Sabina and Sardis. Veria Phaedrina of Ephesus, Plancia Manga of Perge, and Arkhippe of Kyme.

Sun goddess of the city of Arinna holding her child.

Coin with head of Sinope, Sinop, Hellenistic period, 333-306 B.C.

Perfume bottle in the shape of a woman, Gordion Tumulus II, Phrygian, late 7th-early 6th centuries B.C.

As the monotheistic faith of Christianity become widespread in Anatolia during the Byzantine period, the Virgin Mary featured prominently as the mother of Christ (mother of God) in religious doctrine and imagery. Particularly after the Middle Byzantine period, depictions of Mary began to be seen in the semidome of the apses, which was one of the holiest section of the church.

The famous queens who played a dominant role in the government during the Byzantine period were also patrons of the arts. Helen, mother of Constantine the Great, Theodora, wife of Justinian I, the Empress Zoe and the Empress Eirene of the Middle Byzantine period were not only powerful political figures, but founders of numerous churches and social institutions.

Under the Byzantines women were not equal in the eyes of the law, despite their respected role in the domestic context. However, they were able to own property, and where necessary to manage it themselves.

Turkish Seljuk and Ottoman Periods

(12th Century AD-early 20th Century)

With the advent of Islam, to Anatolia, the image of women in art underwent a fundamental change. Since there was no question of a religious iconography based on imagery in Islam, the religious identity of the woman as goddess, mother of god or saint became a thing of the past. Although şeriat (Islamic law) did not give egual rights to women in marriage, divorce, inheritance or ownership, women were able to wield their judicial rights and the law protected the property rights of women and those in need, such as widows and orphans.

Portrait of Hürrem Sultan, wife of Süleyman the Magnificent, Venetian school, anonymous, 18th century.

The Harem.

Many powerful women of the Ottoman palace greatly influenced the course of history. Members of the imperial dynasty, such as Hürrem, Mihrumah, Nurbanu, Kösem and Turhan Sultans, are remembered not only for their political powers, but as founders of institutions. Several Ottoman women from all stratas of society endowed mosques and cultural and social institutions under the Ottoman vakif (endowment) system. The Tanzimat reforms of 1839 and the resulting modernization of institutions allowed women to enjoy more extensive educational opportunities and to make their voices heard in society. The poets Adile Sultan and Nigar Hanım, the artist Mihri Hanım and the poet and musician Leyla Saz Hanım are examples of women raised in the palace and upper class families. The opportunities and rights which such educated women obtained in the mid-19th century were later extended to women of all social strata with the establishment of the Turkish Republic.

Two piece special day outfit, İstanbul, last quarter of 19th century. Silk satin, lace, tulle, cotton.