Tell me a story of the Silk Road: Mehmed Siyah Kalem Paintings

Kiraz Perinçek Karavit

Little is known about Mehmed Siyah Kalem, a painter who probably lived around 15th century in a rural hinterland of Central Asia exposed to Chinese influence. The paintings attributed to him are now in Topkapi Palace Museum, and these paintings reveal the cultural interactions along the art centers of the Silk Road during the Middle Ages. It is possible to see the whole map of the Silk Road in the mobility of the art subject, artisanship, artist and artwork.

First of all, the art subject is mobile; since these paintings depict nomads and nomadic life. Secondly, artisanship is mobile: the technique used in these paintings is mainly executed by brush and ink and has its origins in the Far East and Western China. The plant used in the paper’s manufacturing also has its origins in northern and western China and the Himalayas. Moreover, the paper production method was traditionally used in Thailand, Nepal and Tibet. Thirdly, the artist is mobile since he is a storyteller wandering from city to city, showing these pictures and telling related stories. And finally, the artwork itself is mobile since the paintings were probably made somewhere in Central Asia, Khurasan and Iran around the 15th century, then placed in the albums of the Aqqoyunlu ruler Yakub Beg whose court was in Tabriz. Finally they ended up in the Ottoman court, Istanbul, around the 16th century.

By examining the transmission of images, styles, iconogrophy, forms, and by extension the possible transfer of symbols, meaning and artistic impact from Chinese sources to Siyah Kalem paintings, we can discover some common motifs existing in Buddhist mural art in northern China.

Monsters, demons, supernatural beings: In the Siyah Kalem paintings, an important feature of the demons is that they have tails. These tails are reminiscent of creatures like snakes or dragons. They bite their “owners” or sometimes, when two demons are fighting, bite the other demon. Another notable feature of the demons is that they have horns. We can see two different kinds of horn: one similar to that of a ram, the other to that of a deer. In some paintings, we see that these demons possessing different kinds of horns are fighting each other. Also important to note is that they have chains or rings on their feet, arms, necks and ears.

These features are very common in Buddhist mural art. Figure 1 is a mural painting from Fugong Temple in Shanxi province dating from Liao to Jin Dynasty (916-1234). The depiction of the Guardian of the East shares some similarities with Siyah Kalem demons. He paints some parts of the body (like the belt and shoulders) as snakes or dragons; moving, biting independent of the “owner”. He also paints chains or rings on different parts of the body. The symbolic meaning of these motifs must further be questioned. It must surely surpass the resemblance of artistic form and style and contain an interaction in the cultural and symbolic meaning level. What is the meaning of rings on different parts of the body? Why do gods have snakes and dragon-like creatures as a part of their body or clothes?

Fig. 1

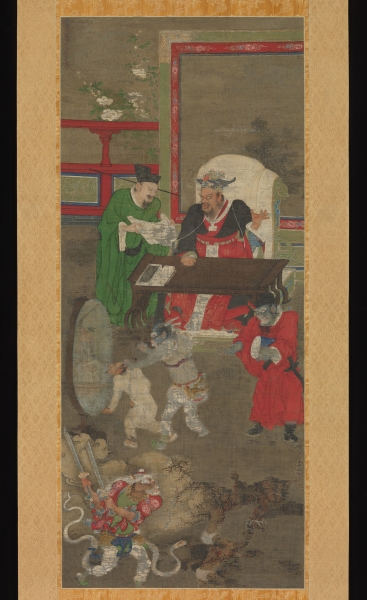

Figure 2 is one of the 10-painting series from the Southern Song period (1127-1279) depicting Ten Kings of Hells. In traditional Chinese culture, Hell consists of several levels in which punishments are carried out on sinners based on their actions in life. We can see in this painting, as with the monsters of Siyah Kalem, horns and snake-tail.

Fig. 2

Knotted cloth, blue cloth: A very central figure in Mehmed Siyah Kalem paintings is blue cloth. The blue cloth seems to be an important element of this tale. There are paintings depicting a black woman showing a blue cloth, some other black people dancing with blue clothes, demons fighting for a blue cloth, a man pulling his animal with a blue cloth, people binding their hats or putting blue cloths on their neck, etc. In some paintings, and interestingly in paintings with demons, the color of the cloth is black and seems to be knotted on the air between two people. This surely has a symbolic meaning.

Interestingly, we encounter knotted clothes and flying clothes of gods and apsaras in many Buddhist wall paintings, and the color blue is very common for these clothes. The blue cloth is still a very important element of the shamanistic cairn tradition “ovoo” in Mongolia. Worshippers of the sky place a tree branch or a stick in the ovoo and tie a blue “khadak” a ceremonial silk scarf symbolizing open sky and the sky spirit Tengri. The “khadak” originated from Tibetan culture, and was later adopted by the countries (Mongolia, Bhutan, Nepal, some part of Russia and India) where Tibetan Buddhism spread. Often silk, a khadak is used in important ceremonies such as for birth, wedding and funeral as a symbol of purity and compassion.

Another interesting aspect related to this motif is that after the death of Buddha, among his bodily relics, his turban also is worshipped, as an enlightenment symbol and princely figure. Depiction of turban worship, symbolizing a kind of adoration and affection for Buddha, can be seen in Gandharan art and in some Buddhist caves in Xinjiang region. Figure 3 is the Gandharan fragment depicting the worship of Siddhartha’s turban in Peshawar Museum, Pakistan. The turban is placed on a cushion that rests on a throne covered with a textile. The knotted cloth in front of the cult object is worth of attention.

Fig. 3

Mehmed Siyah Kalem paintings were probably used to illustrate recitations by storytellers who wandered from village to village giving their performances. These recitations must either have been orally transmitted folk stories or religious stories from shamanism, Buddhism or Manichaeism. This oral tradition still continues today in many parts of China. In traditional festivals we encounter even in Beijing the storytellers showing pictures in a box and telling folk tales. Figure 4 is a photograph of a storyteller taken in Beijing in October 2013. The child looks at the pictures shown in the case and listens to the storyteller.

Fig. 4

Future research of Mehmed Siyah Kalem paintings may reveal the cultural interaction among various groups living along the Silk Road on the basis of these common motifs of folk tales and legends. So, this "art travel" beginning in China, continuing through Central Asia and Iran, and finally ending up in Anatolia, will probably find its “oral carrier” too.