CHANGING FASHIONS OF OTTOMAN WOMEN DURING THE SECOND CONSTITUTIONAL PERIOD (1908-1923)

Dr. İ. Elif Mahir Metinsoy

Turkish Cultural Foundation Fellow (2012-2013)

Ph. D. in Contemporary and Modern Turkish History, Universite de Strasbourg Cultures et Societes en Europe (2012) and Boğaziçi University, Atatürk Institute for Modern Turkish History (2012)

The Second Constitutional period in the Ottoman Empire was a critical turning point for Ottoman women’s fashion and clothing styles. During this period, women acquired new rights and liberties, while at the same time the Ottoman society and state started to have new expectations from women. Ottoman women’s new appearance in public life symbolized “liberty,” and Ottoman women symbolized the new constitution and new regime in the imagery of this important political development. However, both Ottoman women and their new appearances in new dresses were more than symbols. Tracing the transformation of the Ottoman state and society in the change of women’s clothing opens new perspectives that help us to better grasp both Ottoman politics and the power of cultural elements like women’s clothing as an active dynamic of social and political change rather than their passive outcome. Social, political and economic conditions, Ottoman modernization and women’s clothing mutually affected and reshaped each other. Women’s clothing changed in this period faster than before, and this change was not a purely socio-political development, but was also represented, reflected and debated in the arts and literature of the time.

The period between 1908 and 1923 also marked the beginning of the 20th century which was especially significant for rapid changes in women’s fashion in Europe and many other regions under Western influence. This was a period marked by the birth of mass fashions. Rather than following their traditional life-styles and wearing traditional garments, women all around the globe started purchasing new and cheaper fashion items produced in great numbers. In those years the masculine and yet elegant style of Coco Chanel had a deep impact on the physical appearance and clothing of women not only in France, but worldwide. During World War I, many women became active in economic life and started working outside their homes, in factories and offices in large numbers to replace conscripted men. These new duties meant also new liberties for women. For instance women showed more interest in doing sports and wore new outfits for this purpose. Their styles were more masculine, casual and simple as a result of their increasing appearance in public life. Especially the 1920s were marked with a short haircut style that is called bob and a less feminine dressing style which made women look more like school boys that is named à la garçonne (Image 1). The “new woman” of the roaring 1920s was thought to be more active in partying and flirting. The stereotype flapper woman with short skirts, short hair and cigarettes was commonly used in the depictions of this modern woman.

All these developments concerning women’s fashion outside the Ottoman Empire had an impact on the dressing styles of Ottoman women as well. Indeed, women’s fashion in the Ottoman Empire changed rapidly at the beginning of the 20thcentury. The clothing styles of the previous centuries, especially the magnificent clothes of the 15thor 16th century Ottoman palace women which heavily used embroideries, silk and precious golden textiles were long forgotten even during the 17th and 18th centuries. Yet, Ottoman style continued to have an impact on Europe, especially among the European elites. This style called Turquerie was an influence in fashion, and also in decoration, arts, literature and even music. From the 19th century onwards, the Ottoman Empire began to have less of an influence on Europe, but rather was influenced by Western clothing and lifestyle. This change started with the uniforms of the Ottoman army and bureaucrats, and continued with women’s clothing which became more modernized and Western in this century. Accordingly, while the new garments that were used in indoor clothing began to gradually look more like European women’s dress, the outdoor clothing changed too. Perceived as a threat to Ottoman social order and therefore restricted by the sultans, Ottoman women resisted these decrees in this century. During the reign of Sultan Selim III, they started wearing their traditional outdoor garment called ferace in colors that were different than which was allowed to them. Likewise, during the reign of Sultan Abdülhamid II, they resisted the decrees that prohibited them to wear çarşaf, which replaced the ferace as a modern and simple outdoors garment of Ottoman women.

Similar developments at the beginning of the 20th century displayed that Ottoman women’s outfits were highly under the influence of European styles. Indeed, women of the Second Constitutional period, particularly in the capital city Istanbul, were closely following Paris fashions thanks to big fashion houses in Pera and Greek Ottoman tailors called modistra, who made house calls. In this period, women’s çarşaf became shorter and tighter, revealing women’s bodily features (Image 2). Furthermore, especially after the Balkan Wars and World War I, Ottoman women’s veils became more transparent or were replaced by umbrellas that women used to hide their faces, only when needed. This had a lot to do with Ottoman women’s increased activity in work life due to the conscription of men to the army. Shorter skirts, comfortable shoes and new accessories related to their educational or professional life such as books for female university students, uniforms or badges for women nurses and army staff or pants for those women street-sweepers of Istanbul were unaccustomed details of this new look. Furthermore, during the Armistice period, just like in Europe and the United States, Ottoman women started to follow short hair fashion of the 1920s. In Istanbul they were also under the influence of Russian refugees who had fled from the Bolshevik army. Russian women, just like the Greek tailors of the previous epoch, set an example of the new European fashions. Ottoman women changed their head covering styles and started using the headscarves called Rusbaşı (Russian head) which was tied at the back of their heads and showed some of their hair and neck (Image 3). Ottoman women also started to watch their weight and do sports to be as fit as Russian women who could easily turn the heads of their men.

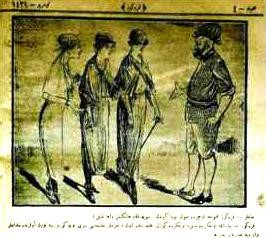

All these developments concerning Ottoman women’s fashion and physical appearance led to debates in the press of the Second Constitutional period. Intellectuals were split among those who favored the Westernized look and those who rejected it. Consequently, women’s new roles and activities in social and economic life became subject of Ottoman art and literature as well. Ottoman artists liked to portray this “new” educated woman as a young woman carrying books, painting pictures or playing Western musical instruments. On the other hand, as an expression of popular criticism, in literature and cartoons, women who followed Paris fashions were debased or mocked (Image 4). They were depicted as extravagant members of their families, wasting their money on fashion items. To the critics they symbolized the moral corruption of the Ottoman society and were even represented as one of the reasons for the demise of the Ottoman Empire. In sum, the change of women’s clothing affected not only women’s appearances, but also influenced and reshaped Ottoman cultural life, the arts, literature, and even the Orientalist view of Ottomans.

Image 1 – Short hair models, İnci, No. 8 (1 September 1919), back page.

Image 2 – Çarşaf models for autumn, İnci, No. 2 (1 March 1919), p. 12.

Image 3 – Rusbaşı (Russian head) style of the Armistice years,

Yeni İnci, No. 2 (July 1922), back page.

Image 4 – A cartoon mocking the modernized outfits of Ottoman women,

Karagöz,

No. 1421 (29 October 1921), p.4.