OTTOMAN WOMEN AND THE VISUAL ARTS

Introduction

The Ottoman Empire, spanning over six centuries, from 1281-1924, was one of the richest and by far the most powerful of all Islamic dynasties. The empire reached its territorial peak during the 17th century, after the reign of its strongest ruler, Suleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520-1566). While the hierarchical structure of the empire fluctuated over the course of its existence, overall, royal women held a relatively high position of status and power, often playing an important role in dynastic politics and society. Yet, instead of active participation in a public arena, their social status was understood within the confines of private spaces. Women therefore found ways to be publicly recognized and to demonstrate their individual power without being physically present. This was accomplished through patronage of the arts, most specifically architecture, and through their involvement in textile production.

|

The Ottoman Empire at its height, around 1680. It encompassed present-day Turkey, Greece, parts of Eastern Europe, the northern coast of Africa from Morocco to Egypt, and the holy cities of Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem. |

Public and Private Space for Ottoman Women

The idea of public and private in Islamic societies can be quite different from western notions of space. The harem and the practice of seclusion were important aspects of life in the Ottoman Empire, but are often misunderstood by westerners. In the Ottoman Empire, social and political life for the upper class occurred solely within private spaces for men as well as women, while poor men and women lived and worked side by side in public spaces. Therefore, an individual's seclusion demonstrated both social and political status, and in no way was seclusion solely a female experience. In fact, the sultan's power was demonstrated through his seclusion within the harem; women were able to gain political and social power according to their proximity to him.

The Ottoman Harem

The term "harem" is derived from the Arabic root h-r-m, which means, among other things, sacred, and is a term of respect referring to religious purity. The harem of an Ottoman household, which was common only among the wealthy, did not simply consist of a male head and his wives, but included children, widowed sisters or mothers, and female servants as well. In the West, it is generally seen as a sexual place of female oppression where women lacked power and men were forbidden. Quite contrary to these beliefs, the harem was a patriarchal support system and the center of family and social life. Family politics, rather than sex, was the main force behind the harem and men and women both occupied the space. The Imperial Harem (harem-i humayun, the harem of the sultan), though similar in idea, was much more complex, and was an extremely organized system of administration and hierarchy.

Unlike structures of western government, where increased power often means increased public profiles, power in the Imperial Harem was linked to seclusion, as it demonstrated one's proximity to the sultan. Over the centuries of Ottoman rule, the sultan became increasingly secluded within the harem and the princes, or future rulers, stayed within its confines as well. This allowed royal women a greater ability to participate in politics. The valide sultan ruled the harem, with much influence over her sons, and played an important role in state affairs between rulers. The valide sultans were so powerful that the later Ottoman period has been referred to by some as "The Age of Women."

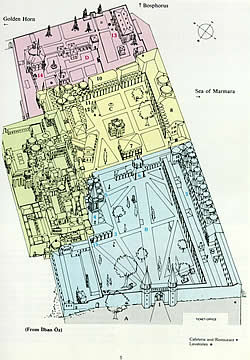

The Topkapi Harem

For centuries, the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul was the center of Ottoman politics and it was here, around 1620, that the harem's power hierarchy was developed. Individuals within the harem were divided into three groups: the elite, the administrative, and the rank-and-file services. The harem had at this point grown from a dynastic residence to a training institution for men and women to become the Ottoman elite under the sultan. Boys and girls were sent respectively to the gate and the harem, both slave training institutions. Women and men held administrative positions, and the institution could be seen as two complementary systems - one male and one female - which paralleled each other in governing and managing.

A strong power hierarchy was present among the elite within the harem. An individual's status was demonstrated through authority and wealth, which was distributed accordingly. The valide sultan maintained a superior position over all others. She was followed in status and stipend by the haseki, or favorite concubine to the sultan. The royal concubines were next, followed by the princes and princesses, who were not given much status or particularly large stipends. The sultan's wet nurse, the daye khatun, was considered a member of the family elite, as well as the ketkhuda khatun, who played an important administrative role as the harem stewardess. Both received generous stipends and patronized charitable works which demonstrated their status among the dynastic elite.

The architecture of the Topkapi depicts spacially the ideological power structure and hierarchies of the post-1620 Ottoman harem. Size and opulence (or lack thereof) of living quarters coincided with the rank and stature of the inhabitant, and space within the harem was rigidly controlled. The valide sultan's quarters were centrally situated, as she was the head of the harem and from here could supervise both the family apartments and those belonging to servants and administrators. Her position, and the positions of other administrative women within the harem, exemplifies the powerful roles women in elite Ottoman society were able to play. The harem was the center of political life in Ottoman society, thus the role of women was quite prominent in this effect.

|

|

|

|

| Above: Topkapi Floor Plan. Click on Image for layout descriptions and further information. |

|

|

|

| Right Top: Chambers of the Royal Wives, Topkapi Palace Harem. |

|

|

| Right Bottom, Sultan's Throne Room, Topkapi Palace Harem. |

|

|

Ottoman Women and Textiles

Textile Production

During the Ottoman Empire, the economy was largely based on textile production and trade, which the rulers subsidized and regulated. Carpets, silks, cottons, and other luxury goods comprised the wealth of commodities that through trade, mainly with Europe, led to the maintenance of a healthy economy during the Ottoman Empire. Women played an extremely important role in this textile economy, and the outlet they found in embriodery and cloth spinning allowed for an undeniable amount of power and financial independance in a world dominated by men.

During the Ottoman Empire, the economy was largely based on textile production and trade, which the rulers subsidized and regulated. Carpets, silks, cottons, and other luxury goods comprised the wealth of commodities that through trade, mainly with Europe, led to the maintenance of a healthy economy during the Ottoman Empire. Women played an extremely important role in this textile economy, and the outlet they found in embriodery and cloth spinning allowed for an undeniable amount of power and financial independance in a world dominated by men.

One significant aspect of the Ottoman textile industry involving women was embroidery, both domestic and in workshops. Most of the embroidery in the empire came from the Imperial Harem and other harems of high officials, from the workshops and factories, and from domestic women working independantly in their homes. The latter group was the largest and produced the most unique and intricate works, with a widespread reputation for excellence.

One significant aspect of the Ottoman textile industry involving women was embroidery, both domestic and in workshops. Most of the embroidery in the empire came from the Imperial Harem and other harems of high officials, from the workshops and factories, and from domestic women working independantly in their homes. The latter group was the largest and produced the most unique and intricate works, with a widespread reputation for excellence.  Ottoman women in the city centers, confined to their homes by social convention, used embroidery mainly to pass the time, but the beautiful pieces they produced became a source of income as well, thereby allowing them some financial independance. Because these women were often working individually and could support themselves, they actually had the authority and respect to be able to refuse commissions if they so wished, even from the Imperial Palace.

Ottoman women in the city centers, confined to their homes by social convention, used embroidery mainly to pass the time, but the beautiful pieces they produced became a source of income as well, thereby allowing them some financial independance. Because these women were often working individually and could support themselves, they actually had the authority and respect to be able to refuse commissions if they so wished, even from the Imperial Palace.

Dress

The skill of embroidery was a major part of the education of young girls in the Ottoman Empire, and as these girls grew and became more adept at their work, they could set up small informal schools to teach younger girls embroidery. This was another way for women to support themselves and be productive in society, properly bringing up the young women and providing a new generation of expert embroiderers. In addition to embroidering, this practice of gathering together provided a social outlet, which allowed them to socialize, gossip, and take tea. Women were not involved simply with embroidery, but also with spinning cotton cloth used both in trade and in their own homes for headscarves, bed linens, towels, and clothes. They invested much time and effort in creating these garments, and thus took great pride in their appearance, using clothing to identify themselves within their society by class and religion. Because women were the ones embroidering the majority of the clothes, they had a direct influence on the fashions of the day.  Due to active trade with Europe, many European influences in Ottoman fashion began in the 1700's; there are many accounts of these interactions in traveler's journals and letters. The basic uniform of loose pants (salvar), a loose shirt (gomelek), and robes (entari) started to see European touches of lace collars and cuffs, and would be accessorized with gloves, buttons, and parasols. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the wife of the English ambassador to Turkey, spent two years in Turkey in the early 1700's, and during her stay wrote many letters decribing the clothing and habits of Turkish women:

Due to active trade with Europe, many European influences in Ottoman fashion began in the 1700's; there are many accounts of these interactions in traveler's journals and letters. The basic uniform of loose pants (salvar), a loose shirt (gomelek), and robes (entari) started to see European touches of lace collars and cuffs, and would be accessorized with gloves, buttons, and parasols. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the wife of the English ambassador to Turkey, spent two years in Turkey in the early 1700's, and during her stay wrote many letters decribing the clothing and habits of Turkish women:

"The first piece of my dresse is a pair of drawers, very full, that reach to my shoes and conceal the legs...They are of a thin rose colour damask brocaded with silver flowers, my shoes of white kid Leather embrodier'd with Gold. Over this hangs my Smock of a fine white silk Gause edg'd with Emroidery...The Antery is a wastcoat made close to the shape, of white and Gold damask, with very long sleeves....My Caftan of the same stuff with my Drawers is a robe exactly fited to my shape and reaching my feet..." (Halsband 326).

"The first piece of my dresse is a pair of drawers, very full, that reach to my shoes and conceal the legs...They are of a thin rose colour damask brocaded with silver flowers, my shoes of white kid Leather embrodier'd with Gold. Over this hangs my Smock of a fine white silk Gause edg'd with Emroidery...The Antery is a wastcoat made close to the shape, of white and Gold damask, with very long sleeves....My Caftan of the same stuff with my Drawers is a robe exactly fited to my shape and reaching my feet..." (Halsband 326).

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu in Turkish Dress.

Architectural Patronage of Royal Ottoman Women

From the beginning of the dynasty, the rulers and members of the elite class built private palaces and public buildings such as mosques, madrasas, hospitals, and caravanserais with waqfs to endow their projects. By providing public spaces for the people of their empire, the elite not only demonstrated their political and social status; they often also expressed religious commitment and drew attention to significant locations in the empire. Architectural patronage was viewed as an important pious act that would earn patrons rewards in heaven. Female patronage began shortly after the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople (Istanbul) in 1453, under the rule of Mehmed I. Female patrons were sometimes sultans' wives, princesses, and most principally, the valide sultans. A unifying characteristic of these female patrons was motherhood; aside from Hurrem Sultan, Suleyman's wife, who was in the midst of her childbearing years when she became an architectural patron, women generally had to be finished with childbearing and rearing to have the seniority status that enabled them to build. Here, we will provide information about a few of the most notable royal women architectural patrons and their projects, but it is important to recognize that there were many more throughout the Ottoman Empire.

Hurrem Sultan (d. 1558)

Hurrem Sultan was the first especially powerful woman of the Ottoman dynasty. She rose to prominence after becoming the first concubine to legally marry a Sultan and move with her family and the harem into the Topkapi Palace in 1534. The extent of her architectural patronage is great, including new buildings as well as restorations. While there were female patrons before Hurrem, none made contributions as extensive and central to the empire; in fact, she was the first female to patronize works in Istanbul, as opposed to solely the provincial towns. Her most significant architectural contribution is known as the Haseki Hurrem Kulliye in Istanbul (1540). Large and centrally located, it was comprised of various religious and social structures: originally, a mosque, madrasa, Quran school (mekteb), and soup kitchen (imaret). In the 1550's she added a hospital for women and a double bathhouse (hammam). This complex helps illustrate that, overall, Hurrem Sultan's significance as a patron lies primarily in the fact that the extent of her visual display of status and power was unprecedented from a woman in the Ottoman dynasty.

| Haseki Hurrem Hammam, Istanbul |

|

Mihrimah Sultan (d. 1578)

The daughter of Hurrem and Suleyman, Princess Mihrimah Sultan, was along with her mother, probably the most notable female architectural patron of the Ottoman Empire. Various mosques and charitable foundations in Istanbul were provided by Mihrimah, who devoted a majority of her wealth to architectural patronage. Her mosque (circa 1562-65) at the entrance to Edirne was designed by the most prominent architect of the Empire, Sinan, and is renowned for its architectural innovation. Like Hurrem's complex, it consists not only of a mosque, but also a double hammam, imaret, and madrasa, as well as extensive courtyards and gardens. However, its unique, challenging position on the top of a hill and its unprecedented spaciousness and luminosity make it architecturally remarkable. That such a significant work was patronized by a woman supports the belief that royal women clearly enjoyed some position of authority and opportunity in society. In fact, women's structures were often more innovative than the typically monumental but conservative works by men.

|

|

|

Above: Exterior view, Mihrimah Sultan Mosque, Istanbul

Right: Interior view of qibla wall

|

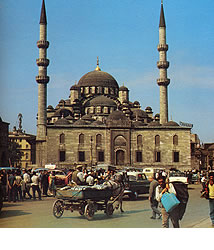

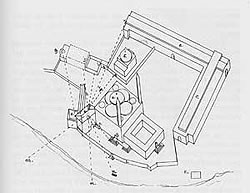

Safiye Sultan and the later Valide Sultans

During the reign of her son, Mehmed III (r. 1595-1603), Safiye's great power as valide sultan marked the beginning of the "Reign of Women" in the Ottoman Dynasty, a period of almost 100 years during which women were arguably the most powerful members of the royal palace. In 1598, she initiated the building of what is known as the Yeni Valide Mosque (or, the New Mosque of the Valide Sultans) in Istanbul, but when Mehmed III died in 1603, Ahmed I took over the throne, sending her off, and the project was left unfinished. Kosem Maypeyker Sultan, Ahmed I's widow, was the next valide sultan to resume the construction of the complex during her son's reign, which began in 1623. Building was again disrupted when she was killed by her daughter-in-law, Hatice Turhan Sultan, who then came to power and continued the project through to its completion in 1665. Like the kulliye of Haseki Hurrem, this significant complex was large and centrally located, made up of various buildings with both religious and social functions. Most interesting about this work, however, is its assymetrical, and thus atypical, layout. Not only was this plan innovative, well-suited to and expressive of the patrons' lifestyles, but the pavilion of the valide sultan (the Hunkar Kasri), and the ramp leading to it, speak of her powerful status and authority. From this building, the layout of the Yeni Valide Mosque gave the valide sultan the power of the gaze; in other words, while as a woman she did not have physical access to all of the surrounding areas, this complex privileged her with visual access, putting her in a more powerful position than her community from whom she was concealed. Therefore, the Yeni Valide Mosque asserts the power that was held by the valide sultans during this period of the Ottoman reign.

|

|

Exterior View of Yeni Valide Mosque, Istanbul

|

| |

| |

|

Below: The courtyard of the

Yeni Valide Mosque

|

Above: The sight lines from the Hunkar Kasri extend out in various directions, over the surrounding areas. This illustrates how the complex gave the valide sultan visual access to places that were physically inaccessible.

|

Glossary

Caravanserai: a rest place for travelers that consisted of inexpensive lodging, food, and shelter for animals

Eunuch: a castrated male slave with elevated status within the Imperial Palace

Kulliye: a patronized architectural complex attributed to the royal family and consisting of buildings with both religious and secular functions

Madrasa: a religious school

Sultan: religious and political leader, the head of the Empire

Valide Sultan: the Queen Mother, or the sultan's mother

Waqf: the endowment of charitable foundations, or the deeds for them, established by wealthy patrons

Reference: http://www.skidmore.edu/academics/