Thermal Baths in Buda in the Ottoman Period of Hungary

Adrienn Papp

Turkish Cultural Foundation Fellow (2012-2013)

Ph.D. Candidate, Archaeological history, Eötvös Lorand University of Science

Archaeologist, Budapest History Museum, Department of Middle Ages Research

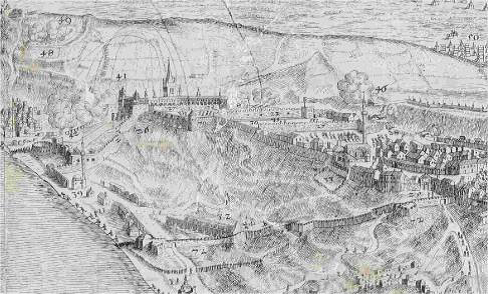

The central zone of contemporary Hungary was part of the Ottoman Empire between 1541 and 1690. Having been occupied by the Ottoman forces between 1541 and 1686, Buda, which is part of Budapest today, became the seat of the new province of Buda (vilayet). As a result, many buildings built by the Ottomans in the 16th century can be identified in contemporary Budapest. In addition, archaeological excavations discovered artifacts dating to the same period (16th and 17th centuries). The cluster of standing edifices includes four thermal baths that were built in the 16th century and have been in use ever since. Only these four baths, called Rudas, Rác, Király and Császár Bath today, functioned in Buda in the Ottoman Period of Hungary. Three of these were reconstructed between 2004 and 2009. Archaeological excavations and national monumental research were also implemented in the course of their reconstruction. Thence in-depth knowledge of their condition dating to the Ottoman Period as well as of their environment in the same era has been acquired.

The townscape of Buda significantly changed in consequence of the Ottoman occupation. The royal seat became the hub of a border province in a giant empire. It was no longer the town of a king but of a newcoming ruler of a province. The Christian cultural circle of the Kingdom of Hungary and the Muslim one of the Ottoman Empire crucially deviated from each other. Therefore, the reconstruction of Buda started very early: Christian churches were built into djamis, and new buildings, such as djamis (mosques), schools, monasteries, and baths, related to the Ottoman institutional framework appeared. During 150 years of Ottoman rule, the town of Buda laid adjacent to the frontline, thus significant armed forces were stationed there. Due to its prestigious function, Buda survived many sieges.

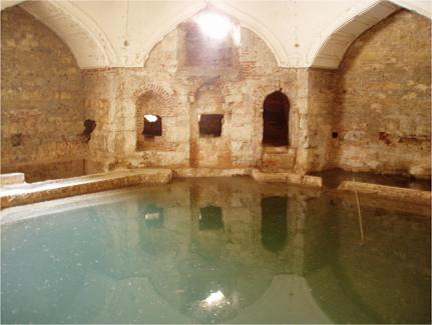

Natural thermal sources can be located in particular clusters south and north of the castle of Buda on the bank of River Danube. Peoples living in this neighborhood took advantage of these natural thermal sources since around the beginning of chronology. Having had a notable bathing culture, the Ottoman Empire built thermal baths next to these thermal sources still in use nowadays. Travelers who visited Buda in the 16th and 17th centuries recalled the fascinating baths buildings and the beneficial effects of their waters. These baths were so much part of the town that their original function was kept after the re-occupation wars. They also experienced their renaissance in the 19th century, when huge bathing complexes were built around them and so they were integrated totally. Miraculously, the cupolas of the hot rooms survived the air raids in World War II. As a result, there are four baths in Buda, where bathers can enjoy the spatial experience of the warm and hot rooms dating to the 16th century. We know the least of the vestibules; these no longer exist, because the wars in the 17th century and World War II destroyed them.

Three of four Ottoman baths in Buda were built by Sokollu Mustafa Pasha of Buda in the 1570s. He acquired the fourth one. All four were part of the pasha’s gracious waqf (inalienable religious endowment). Mustafa, the Pasha of Buda was the nephew of Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha. His türbe (mausoleum) that was built by Mimar Sinan, the most outstanding architect of classic Ottoman architecture, stood in Buda. This shows that Mustafa Pasha considered Buda to have been a key town for him and his family. He ordered constructions in Buda accordingly: four djamis, two medreses, three baths, and two caravanserais were erected. The baths have been representing the relatively undamaged memorabilia of this large-scale work. The baths did not stand singly: djamis, caravanserais and monasteries laid nearby them. Also, new urbanized areas evolved around them. Assessing the sizes of the baths, it instantaneously strikes the eye that Rudas and Császár are a lot bigger than an average bath, and their architectural character is special as well. Rudas Bath (called Yeşil direkli ilica, to say “Green Columned Bath” in the Ottoman Period) encloses a hot room of which central dome is propped with eight columns. The octagonal marble pool lies between them. The corners of the hall are stalactite-decorated. Very few columned baths were built in the Ottoman Empire: there are two in Istanbul, one of them is associated with Sultan Suleiman, the other with Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha. The latter

one is also called “Green Columned Bath”.

Travelers in the 16th and 17th centuries marveled the beauty of Császár Bath the most. I have not identified any analogue to the extremely convoluted plan arrangement of this bath. According to the descriptions, lion decorated vents released water into the pool. Nothing of these has survived times regretfully.

Although Rác Bath is a lot smaller than the two previous ones, its size equals to that of an average Ottoman bath. Its specialty is that it comprised three pools, and its water was of so good quality that it was recommended to cure many diseases. Even today, this water springs from a 12 meter long chasm that stretches underneath the vestibule of the building dating to the Ottoman Period.

Exhaustive archaeological investigation discovered sections of the authentic stone floor of the buildings and the original ceramic water pipes that stretched within the walls and conveyed water to the wall fountains. Layers of the wall plaster applied in the 16th and 17th centuries were also unveiled, and so were the drain system for water drain and the wooden poles placed underneath the walls. Despite the lack of any chronogram, the latter poles enabled the determination of the construction date (year!) of the baths accurately.

Based on the foregoing, we know accurately the visual aspect and operation of the baths as they were in the 16th and 17th centuries. We might even complete the digital reconstruction of these edifices. Since these features dating to the 16th and 17th century can be distinguished confidently from constructions carried out in the New Age, I am in a scholarly affirmative position to provide a grounded standpoint with other researchers as well.