Orthodox Christians and Muslims in Nineteenth-Century Cappadocian Villages.Everyday Life, Languages, Culture and Socio-economic Relations

Aude Aylin de Tapia

Turkish Cultural Foundation Fellow (2012-2013)

Ph.D. Candidate, Ottoman History, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), Paris

Historiography on Ottoman society has been inclined to study different religious communities (the millets) separately while neglecting the interrelations and exchanges between them at the everyday life level. In Cappadocia, a region characterized by the huge diversity and mixity of religious communities, the long nineteenth century is marked by transformations brought about by reformism by the independence of Greece and the process of Hellenization of Anatolian Orthodox Christians it led to, by the massive movement of emigration from Cappadocia to coast cities of the Empire and especially to Istanbul and finally, in 1920s, by the exchange of population, which puts an end to eight centuries of Muslim/Christian cohabitation in the area. During this whole period, Cappadocia will be the place of interesting evolutions in the relations between Muslims and Christians, evolutions which are observable in all the fields of everyday life.

Muslims and Christians, Turkish-speakers and Greek-speakers

In Cappadocia, region that can be defined by a square delimited by Aksaray, Niğde, Kayseri and Nevşehir/Ürgüp, the two main religious communities were the Muslims and the Orthodox Christians. Most Christian communities were Turkish-speaking (they are called commonly “Karamanli” while several communities, especially in the area of Niğde, Malakopi (nowadays Derinkuyu) and Farassa, were speaking various dialects, that were considered to be archaic forms of Greek language. This linguistic diversity is interesting to put into perspective with the capacity of being in relations with Muslim communities. But actually, according to several narratives of visitors in the beginning of the twentieth century and of exchanged people interviewed by the Center of Asia Minor Studies (Athens), in addition to their mother tongue, a large part of the Cappadocian population had basic knowledge of Greek or of Turkish. Thus the language barrier appears to be not so difficult to overcome. Besides, when one studies relations between Greek-speaking Christian communities and Muslims, he can see that, in most cases, they had almost as much relations as Turkish-speaking communities.

Two compartmentalized communities?

Muslim and Christian population are often presented as two compartmentalized groups with clear boundaries. This traditional picture is certainly brought by the fact that, officially, each group had its own internal organization and administration. However, in Cappadocia, an area where they cohabited since several centuries, this administrative division was not really determining everyday life. People from both communities lived in a continual relation, economic, social as well as friendly, cultural and even religious. As a result, intercommunity relations were getting the tempo in the life of Cappadocian villages.

Living on a same territory

We often describe ottoman villages and towns with mahalles (districts) where each community lived separately but in many cappadocian villages, this separation was not so obvious. In many mixed villages, there was often a church localized in a Muslim mahalle but which was still used by Christians. For instance, in the small village of Keçiağaç (area of Niğde), the new church of Haralambos has been built in the 1850s at the heart of the Muslim mahalle. This new church was of course used by Christians who, consequently went regularly through the Muslim mahalle. Moreover, several Christian families lived near the church, in the middle of Muslim houses. Consequently, geographically, the borders of Muslims and Christians mahalle were not so hermetic.

Economy does not know community borders

Fields of economy, from agriculture to trade, was one of the main grounds for relations. The main activity in a rural area as Cappadocia was, of course, agriculture and farming. Especially during the second half of the nineteenth century, when Christian men left their villages for immigrating in Istanbul, thanks to the money sent by immigrants, the families remaining in villages employed Muslims for working on their lands, helping to housekeeping, taking care of cattle… For instance, Aleixis Sevnikoglou from Ağirnas explains that many Muslims worked on the Christian farmlands or vineyards for 3 liras per year. [KMS, File ΚΠ51 Agirnas]

Christians of Cappadocia were famous for their handicraft, especially as stone masons or carpenters. The British traveler, Ramsay, with some meprising touch towards Muslims, summarized the situation as following: If a Turk lives in anything better built than a hut, I have always found that it is constructed by a Greek. If a Turkish village requires a fountain with its aqueduct, a Greek workman is employed to make it”. [Ramsay, William Mitchell. Impressions of Turkey During Twelve Years Wanderings, 1897, p.22].

Trade on more or less large distances, through the nineteenth century, became one of the most important economic activities of Christian population of Cappadocia. Immigration, especially to Istanbul but also to Izmir, Adana or Samsun, allowed the development of trade among immigrants who, through investments, became the main economic actors of Cappadocia even though they did not lived in the area. We found also interesting cases of partnership between Christians and Muslims. But the main consequence on the region was that, thanks to their economic success, Christian immigrants were able to invest in their native land and local population, Christians, but also Muslims, could benefit from these investment.

Cultural and religious sharing

In Cappadocia, a territory where religious mixity was so intertwined and where the religious past was so engraved in landscape, local popular culture often largely transcended the supposed clear borders between Christianity and Islam. Consequently, churches were often privileged places of worship for Muslims as well as Muslim tekke and türbe were often visited by Christians. Women were particularly attracted by this kind of beliefs. Often, they were the main participants during cults of saints and they regularly invited priests or imams at home for blessing children, ill family members, or simply salt, water and bred.

One of the most obvious examples is the veneration of local saints by members o both religious communities. Most of the time, this cult of saint was practiced in ancient underground churches where relics were exposed. In Malakopi, the underground church called St Anargyr was visited by Christians as well as by Muslims for its thaumaturgy benefits. In the same way, several türbe of Muslim saints and tekke were frequented by Christians who came for blessing. The most renowned shared worship place was the Church of St Mamas, also called Mamason Tekkesi – its double name shows in sine the paradoxical situation of this place between Christianity and Islam – for which Hasluck described the cult as “possibly the most extraordinary case of an ambiguous cult in Asia Minor […] At the east end of the church stood a Holy table (at which itinerant Christian priests officiate), with a picture of St Mamas, while in the south wall was a mihrab for the Turks”. [Hasluck, Frederick William. Christianity and Islam under the Sultans.. Vol. II. 1929.] There was no partition between the Christians and the Muslims, but the latter, while at their prayers, turned the picture from them. The bones of the saint, discovered on the site, were shown in a bow and work miracles for Christians and Muslims: sick people were also cured by wearing a necklet preserved as a relic. The sanctuary was tended by a Muslim, first the landowner and then a dervish who lived next to this church-tekke. Beyond cult of saints, there were many beliefs and celebrations shared by Christians and Muslims such as processions for making rain gathering Muslims and Christians and led by a priest and a hodja together.

The relations described in the previous paragraphs are very few examples of all the kinds of relations that could have Muslims and Christians living in Cappadocia. These relations can be imagined as numerous doors on official borders imposed by the official organization of the ottoman society. There are of course exceptions and limits to this everyday together life, times when borders reappeared or places where they never disappeared. When tensions appeared, especially during wars, these doors could be closed for a while. However, more you were far away from main centers, more they seemed to be maintained wide-opened. On the other hand, examples of villages more withdrawn into themselves – such as the Christian villages of Misti (region of Niğde) or Farassa (North slope of Taurus mountains) where the entrance of foreigners was forbidden or marriages arranged only with people from the surrounding hellenophone villages – show that borders are not systematically transcended.

However, by examining the ways in which people reappropriate rules, administrative organization, official religion or culture in everyday situations, it is possible to say that ordinary people, especially in a rural context, far away from a real control of powers (political as well as religious powers) had many opportunities of transcending rules and practices that institutions sought to impose, of transcending official borders of the community system and of living in the unity of their village rather than within the narrow borders of the religious group they belonged to.

Fig. 1 Royal doors from the Prodromos Monastery in Zincidere near Kayseri, 18th century. The monastery, which can be identified with the Byzantine Flavianon Monastery, was the most important religious and cultural centre in Cappadocia, housing a school from 1844 and from 1882 the Zincidere Seminary. Exhibited at the Byzantine and Christian Museum of Athens.

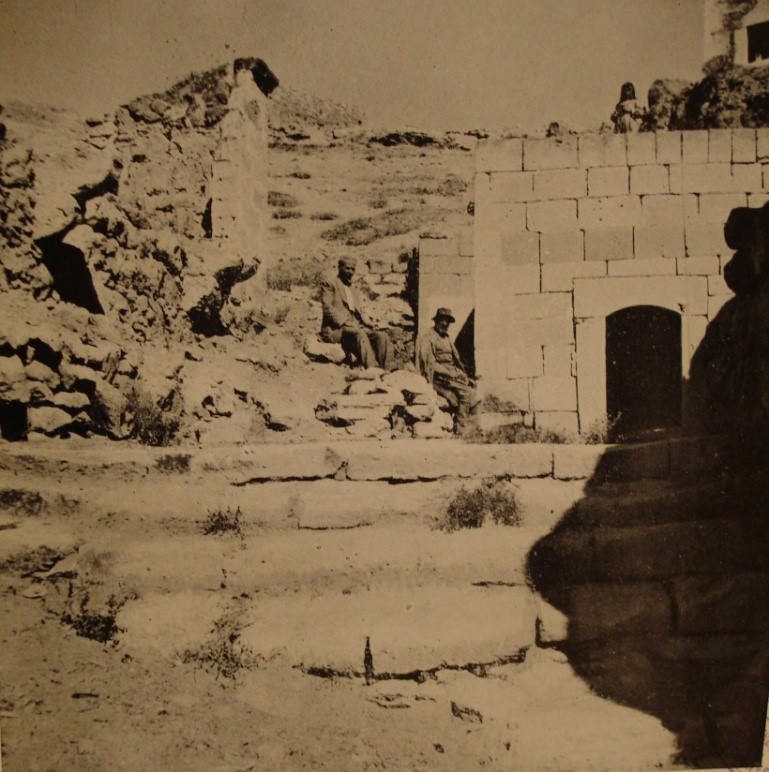

Fig. 2 Mamason Chruch/Tekke. Entrance of the Church/Tekke of Mamason. Near the entrance, the last representative of the dervish order taking care of the worship place. [Photography of Sofia Anastasiadi, Center of Asia minor Studies]

Fig. 3 Malakopi (today’s Derinkuyu) On the top of the entrance, the inscription: “This sacred church of St Theodoros Trion Agios has been built under the auspice of the Parishah Sultan Abdülmecid Han, with the blessing of Aziz İkonion (metropoliti) Neofitos Efendi and thanks to the donations of the Christian inhabitants of Malakopi, under the direction of the architect Kiriako Papadopoulos Efendi from Chaldia. The Church has been blessed and consecrated to St Theodoros. St Theodoros bless the country and protects it from dangers. Amin. Year 1858 May 15.”

Fig. 4 Icon of Saint Theodoros and of the miracle of the kollyva (boiled wheat). Painted by Ilias Sotiriadis, with texts in Karamanli-Turkish. From Cappadocia, 1869. Exhibited at the Byzantine and Christian Museum of Athens